Education, Inheritance, and the Long Road to Dojran

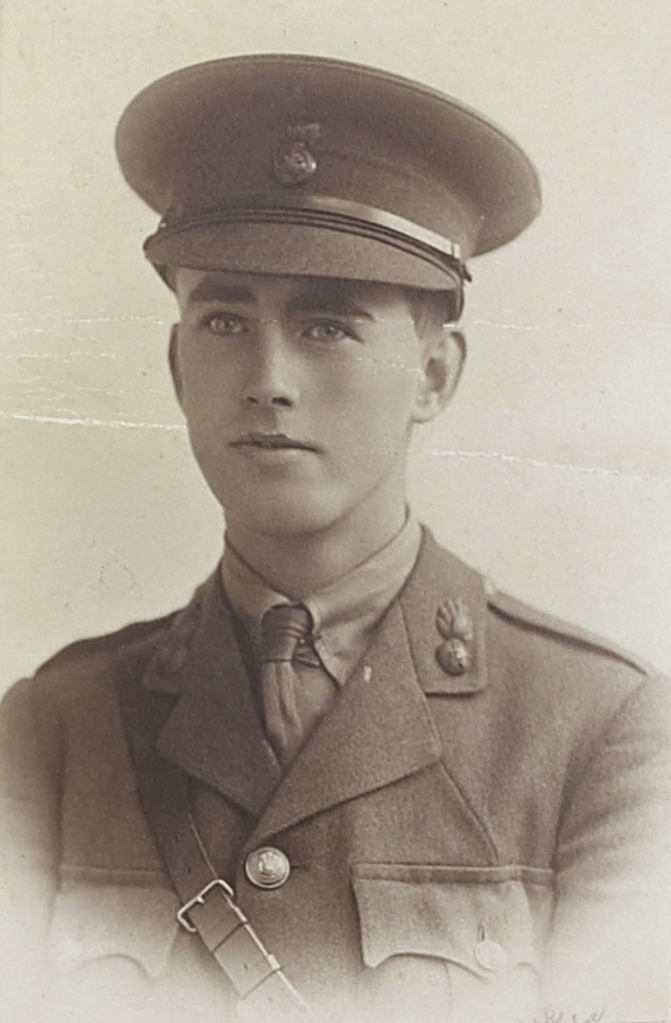

The life of Hugh Wynn Wilding Jones sits at the intersection of Edwardian inheritance, elite education, and the totalising demands of the First World War. His story is not merely that of a young officer killed in action, but of a man whose life trajectory, intellectual formation, and expected social role were progressively dismantled by prolonged service, illness, and finally by a catastrophic engagement on a forgotten front in the war’s final weeks.

Born on 3 March 1896, Hugh was the eldest son of William and Ellen Marie Wilding-Jones. By convention and expectation, he stood as the intended heir to the Glandwr estate, including Glandwr Hall, a position that carried social weight even as the practical realities of estate management were already shifting in the early twentieth century. The Hall itself had been let from 1905, reflecting the broader pressures on landed families in this period, yet inheritance remained a powerful organising assumption within such families. Hugh’s upbringing was shaped by that expectation of continuity, responsibility, and leadership.

Education, Formation, and Intellectual Promise

Hugh’s education followed a recognisably elite and preparatory route. He attended Marlborough House Preparatory School in Hove before progressing to Tonbridge School, one of England’s leading public schools, where he was a member of the Officer Training Corps. This was not merely an extracurricular activity but an early initiation into the values of discipline, command, and service that defined the Edwardian professional class.

From Tonbridge he went up to Corpus Christi College, Oxford. While no surviving record definitively states his subject, it is reasonable, given family background and later trajectory, to infer that he may have been reading law, a common pathway for men expected to combine professional life with estate responsibility. Contemporary recollections describe him as a capable conversationalist with a quiet humour, thoughtful rather than ostentatious, and intellectually engaged. He was also noted to have poor eyesight, a reminder that the idealised physical image of the officer class often concealed more fragile realities.

Commission and Early Military Service

Hugh applied for a commission in December 1915, at a moment when the British Army had formalised officer selection in response to the war’s escalating demands. His application was supported by the headmaster of Tonbridge School, who vouched for both his educational attainment and his moral character, still considered essential attributes of an officer.

Following officer cadet training at Cambridge, Hugh was commissioned in July 1916 as a Second Lieutenant in the Royal Welsh Fusiliers. He landed in France in September and joined the 1st Battalion. His early service was spent in the trench systems of Flanders and later on the Somme, environments that tested junior officers relentlessly through exposure, fatigue, and responsibility for men under fire.

In January 1917, during operations near Beaumont-Hamel, Hugh led a patrol to link up with neighbouring units under active conditions, an episode recorded in the battalion war diary. Shortly afterwards he was wounded, suffering a gunshot wound to the thigh. While the wound itself was described as superficial, it marked the beginning of a long and debilitating period of illness.

Illness, Convalescence, and Interrupted Duty

Evacuated to England, Hugh’s recovery was complicated by persistent gastrointestinal illness, later described as colitis, compounded by influenza and jaundice. These conditions repeatedly delayed his return to active service and confined him for long periods to light duty with the reserve battalion, first in England and later in Ireland.

This phase of his service is significant. It illustrates the less visible attritional cost of the war, where illness, rather than enemy fire, rendered many officers marginal to frontline operations for months or years at a time. Despite this, Hugh remained in uniform, was promoted to Lieutenant in January 1918, and was eventually declared fit for general service once more.

Salonika and Specialist Responsibility

In mid-1918 Hugh was posted overseas again, this time to the Salonika theatre, joining the 11th Battalion, Royal Welsh Fusiliers. The Salonika front, shaped as much by diplomacy and logistics as by combat, was notorious for heat, disease, and stagnation. Casualties from sickness consistently outnumbered those from action.

Hugh was appointed Lewis Gun Officer, a role of technical and organisational importance. He was responsible for training, coordination, and deployment of light machine gun teams across the battalion, a task that demanded precision, judgement, and calm authority. This posting suggests a level of confidence in his abilities, particularly after his earlier health setbacks.

Dojran and Death

In September 1918 the Allied forces launched a major offensive against Bulgarian positions near Lake Dojran. The terrain was steep, broken by ravines, and heavily fortified. When the 11th Royal Welsh Fusiliers went into action on 18 September, the results were catastrophic. Of twenty officers and nearly five hundred men engaged, only a small fraction emerged unwounded.

Hugh was struck during the advance towards Jumeaux Ravine and The Hilt, areas that had already repelled previous assaults. Evacuated to hospital at Kalamaria, near Salonika, he died of his wounds on 22 September 1918, aged just twenty-two.

He is buried at Mikra British Cemetery, Thessaloniki, far from the Welsh estate he was expected to inherit and the Oxford career he never completed.

Aftermath, Memory, and Loss

Hugh died intestate. His financial affairs were settled by the War Office, and his parents later claimed his campaign medals, the British War Medal and the Victory Medal. More revealing than administrative records, however, are the personal tributes sent to his family. Fellow officers described him as “quietly keen,” deeply liked, and valued beyond measure, a man whose presence mattered in ways that extended beyond formal rank.

His grave bears the inscription chosen by his father, “Of Corpus Christi College, Oxford – dearly loved – deeply mourned.” It is a restrained epitaph, but one that speaks powerfully of unfulfilled promise, private grief, and a future that ended before it could properly begin.

Closing Reflection

A single personal artefact still survives in the family archive. A postcard sent by Hugh to his younger sister, written in his own hand, records his safe arrival and conveys routine family affection, asking that his love be passed on at home. Brief and unselfconscious, it captures him in transition, still anchored in the habits of family life, and unaware of how decisively the war would soon reshape his future.

Hugh Wynn Wilding-Jones was not simply a casualty of a single battle, but of a prolonged war that consumed health, opportunity, and inheritance long before it claimed life itself. As the expected heir to the Glandwr estate, his death represented not only personal loss but the rupture of generational continuity. His story stands as a reminder that the First World War reshaped families and futures as decisively as it redrew maps.

Further reading and acknowledgements

More on Hugh Wynn Wilding-Jones, his family background, and the wider context of the Glandwr estate appears in my book Old Llyfnant Valley Farming Families, where I set his short life alongside the longer patterns of inheritance, education, and local continuity that shaped his generation.

My grateful thanks are also due to fourteeneighteen|research for the thorough work they undertook in reconstructing Hugh’s military career from the surviving service record material, war diaries, and associated archival sources, work which has been invaluable in allowing his service, and his death at Dojran, to be described with accuracy and proper context.