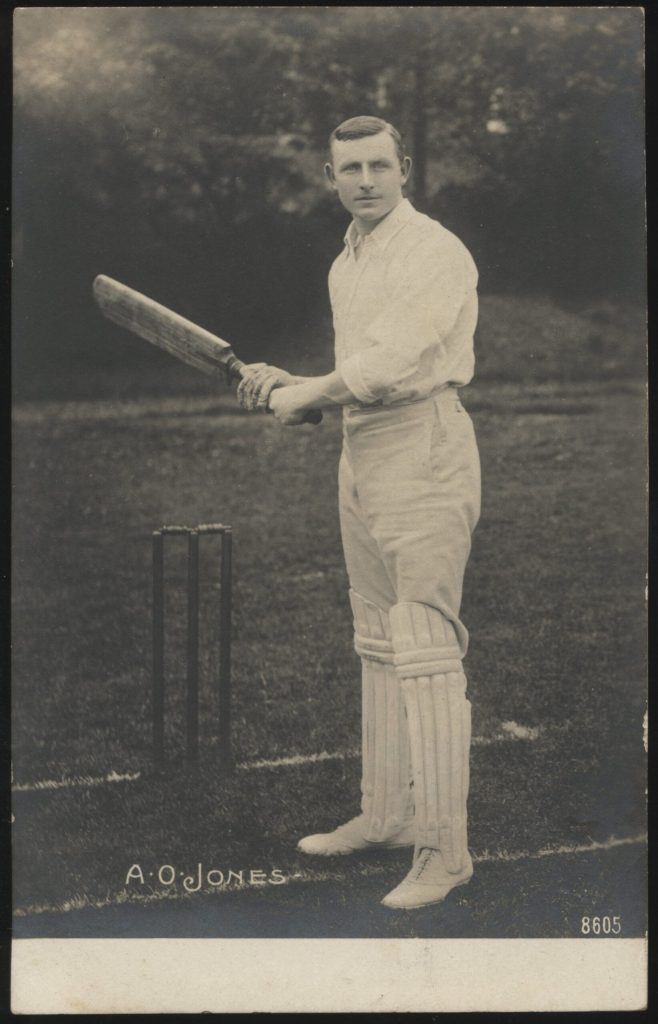

There is something quietly extraordinary about the story of Arthur Owen Jones, one of the most gifted cricketers of the Edwardian era, a man who captained England, broke county records, and reshaped the game through sheer athletic intelligence, yet is now far less widely remembered than he deserves.

What makes his story even more personal, at least for me, is this, Arthur Owen Jones is my cousin. Not an abstract historical curiosity, but family, a name that sits within the same wider lineage, the same inherited map of place, memory, and Welsh rooted identity.

This is the story of a sporting phenomenon, and also, in a very real sense, a family story.

A Welsh-rooted family, and a boy shaped by loss

Arthur was born on 16 August 1872, at the rectory in Shelton, Nottinghamshire. He was the seventh son of the Reverend John Cartwright Jones, and his family heritage linked directly back into Wales, into that Merionethshire world of land, status, and longstanding identity.

But his childhood did not unfold in security. His father died when Arthur was still very young, and the family moved to Bedford. It is hard not to see that early disruption as significant, the sudden loss of stability, the shift of county, the reordering of family life. Victorian Britain was not sentimental about bereavement, children were expected to continue, to cope, to function. Yet experiences like this leave their mark.

And perhaps, for Arthur, sport became both an escape and a stage, a place where effort could be rewarded, and where a boy could remake himself through excellence.

The making of a “gentleman amateur”

Arthur was educated at Bedford Modern School, and later at Market Bosworth Grammar School. He then went to Jesus College, Cambridge, and by 1893 he had won the coveted Cambridge Blue, marking him out as a young man of elite sporting promise.

This was not simply about athletic skill. In late Victorian and Edwardian England, high-level cricket was a social institution, a place where middle and upper class men proved themselves not only physically, but morally and culturally, through restraint, discipline, leadership, and public conduct.

Arthur belonged naturally to this world, and yet he also exceeded it.

Nottinghamshire, the rise of a county legend

Arthur began playing for Nottinghamshire in 1892, and quickly established himself as something far more than a competent county professional.

He became one of the outstanding players of his generation, and in 1900 he was named Wisden Cricketer of the Year, a recognition reserved for those who had genuinely altered the mood of the sport.

In 1903, he produced one of the great innings in county history, 296 not out against Gloucestershire, a Nottinghamshire record that stood for many years. Records always look neat on paper, but anyone who understands batting knows what it represents, concentration under pressure, stamina, technique, judgement, and the mental force to stay undefeated while others break around you.

Then came his greatest leadership feat. In 1907, he captained Nottinghamshire to the County Championship, widely regarded as an unexpected triumph, and the kind of achievement that separates a fine cricketer from a commanding sporting mind.

The greatest fielder of his time, and the invention of “gully”

Arthur’s legacy does not rest on runs alone.

He was widely regarded as the greatest fielder of his era, and often described as one of the finest the sport had ever seen up to that point. There is an artistry to fielding that rarely receives full credit, the anticipation, the speed, the nerve, the ability to turn moments into turning points.

He was even credited with helping to popularise, and in some accounts effectively invent, the fielding position known as “gully”, a tactical refinement that speaks to how sharply he understood angles, edges, and batting intention.

This is the kind of influence that outlasts statistics. Once a position becomes part of cricket’s grammar, it becomes part of the game’s permanent shape.

England captain, and the cruel intervention of illness

Arthur played Test cricket for England between 1899 and 1909, and toured Australia for the Ashes in 1901 to 1902. That tour did not go his way, and his reputation at Test level never quite matched his county greatness.

Then, after his Championship triumph, came the highest honour. He was appointed England captain for the 1907 to 1908 Ashes tour of Australia.

And this is where the story turns harsh.

He arrived in Australia and contracted pneumonia, an illness far more dangerous in that era than it is today. He missed the first three Tests, and although he returned later in the series, England lost. Captains are remembered by results, and illness rarely features in the folklore, but the truth is clear, his chance was compromised before it had properly begun.

It is one of the sport’s quieter tragedies, a man given the supreme role, only for fate to undercut him at the moment he should have been writing his legacy in bold strokes.

A multi-sport man, but cricket was his kingdom

Arthur was also a capable rugby player, and later became a respected referee, widely admired for fairness and judgement.

That detail matters because it shows his temperament. He was not simply an instinctive athlete, he was a man who valued structure and standards, someone who understood sport as something that required integrity as well as performance.

Fame without fortune, the hard truth of his era

Modern audiences assume sporting greatness brings security and wealth.

In Arthur’s world it often did not.

He was famous, admired, decorated with honours, and yet later in life he worked as an insurance salesman, because cricket, in the gentleman amateur era, rarely provided the kind of long-term financial protection that today’s professionals take for granted.

It is an astonishing contrast. England captain, yet living within the ordinary pressures of employment. That single fact says something profound about Edwardian Britain, and about the fragility that sat beneath its polished public surface.

Tuberculosis, decline, and death at only 42

Arthur never truly recovered his full strength. In 1914, he was suffering from tuberculosis, the great lingering killer of the age, a disease that struck across class lines and still carried the feeling of inevitability.

He died on 21 December 1914, aged only 42.

The timing is haunting. The First World War had begun, and the world’s attention was turning towards destruction on a scale previously unimaginable. It is easy to see how the death of a cricketer, even a great one, might fall into the shadow of global catastrophe.

Yet Nottinghamshire did not forget him.

A memorial was raised in his honour, a public act of respect that confirmed what those who watched him already knew, they had seen something rare.

Why this matters, and why I am telling it now

Arthur Owen Jones should not be an obscure name.

He matters because he demonstrates how excellence can burn brightly, and still be vulnerable to illness, circumstance, and the unforgiving memory of history.

He matters because he was not just a record-maker, but an innovator, a thinker on the field, a tactician, and arguably the greatest fielder his age produced.

And he matters, to me, for one more reason.

He was my cousin.

That fact collapses time. It reminds us that history is not just the property of textbooks and archives, it is carried in families, and sometimes it appears in extraordinary forms, an England captain, a sporting pioneer, a man who stood briefly at the summit of public admiration, and then slipped into premature loss.

If we want a single life that captures the Edwardian world in miniature, ambition, reputation, class, discipline, brilliance, vulnerability, Arthur Owen Jones gives us exactly that.

Not merely a great cricketer.

A great human story.