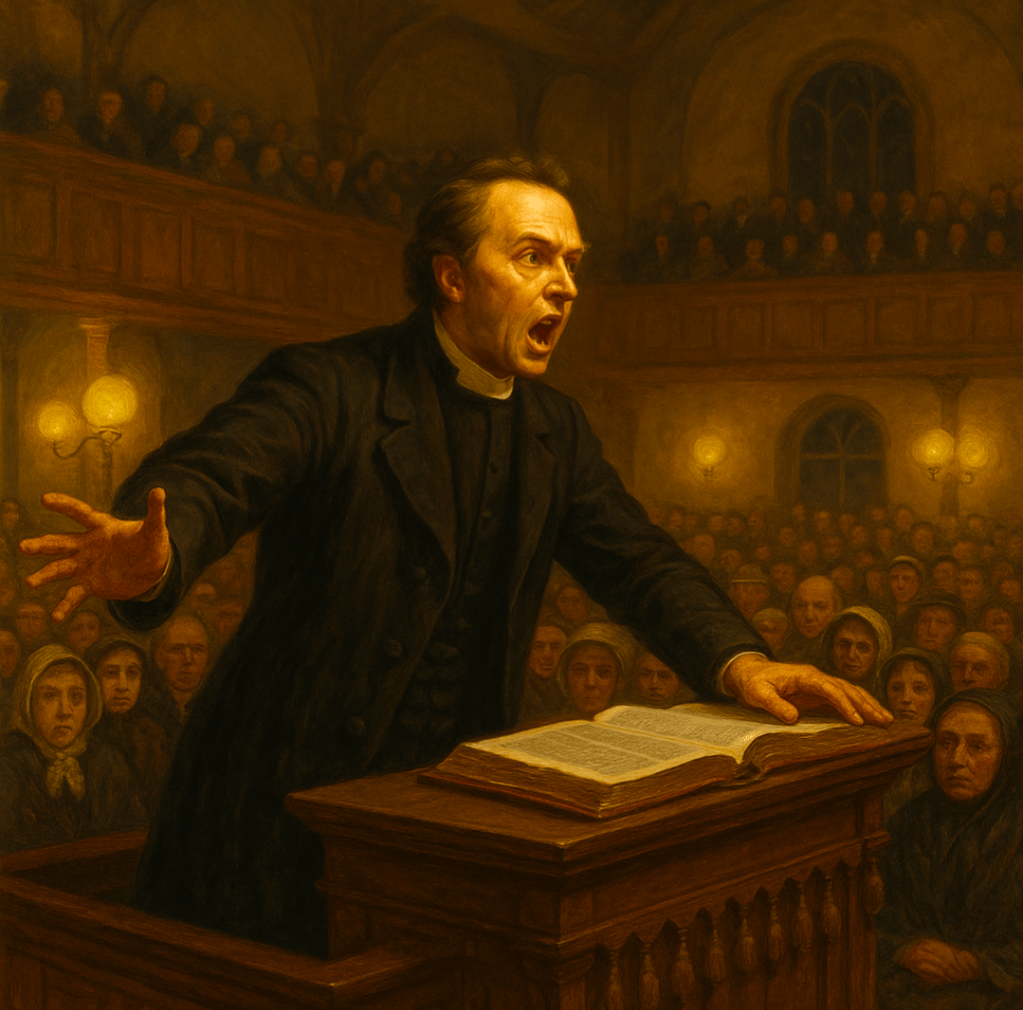

Imagine a Sunday evening in November 1880. Outside, the valley is pitch black, hammered by rain sweeping down from the mountains. But inside the gas-lit chapel, the air is thick with damp wool, peppermint, and anticipation. Five hundred people sit shoulder to shoulder in a silence so taut it hums.

They are not waiting for a politician, a landowner, or a magistrate.

They are waiting for the Preacher.

In the mist-shrouded story of Victorian rural Wales, one figure towered above all others. While England crowned monarchs and elected prime ministers, Wales anointed something quite different.

It had its Ministers.

They were the rock stars, the moral judges, the community leaders — the generals of a spiritual army that shaped a nation.

This is the real story of the Welsh pulpit’s astonishing power.

1. The Pulpit as the People’s Stage

Before cinema, radio, newspapers, or Spotify, the chapel was the theatre of working Wales.

A Sunday sermon was not a polite reading. It was a performance with stakes as high as life and death. Preachers like the one-eyed giant Christmas Evans could silence a quarryman’s cough at the back row. They did not deliver sermons; they inhabited them. They roared, whispered, wept, and brought entire congregations with them.

“He could make you smell the brimstone of hell one minute and feel the soft wing of an angel the next,” wrote one mesmerised listener.

Men walked twenty miles over mountain tracks to hear a great sermon — analysing its rhetoric with the seriousness we reserve today for actors, athletes, or political debates. A dull preacher lost his congregation.

A great one became a national celebrity.

2. The Alchemy of Hwyl

To understand the preacher’s spell, you must understand hwyl.

Often translated as “fervour,” hwyl was far more than emotion. It was a distinctive musical rising of the voice, a rhythmic, melodic incantation that swept through the chapel as the sermon reached its climax.

The pitch rose.

The cadence quickened.

The entire room leaned forward as if pulled by a tide.

Suddenly the congregation erupted — shouts of “Gogoniant!”, sobbing, trembling, frantic amens. For miners and farm labourers whose week was a grind of slate dust, coal smoke, and poverty, this was catharsis.

A moment to feel alive, forgiven, connected, human.

The preacher was not just speaking.

He was conducting the collective soul of the village.

3. The Sêt Fawr: Wales’s Shadow Government

The preacher’s authority extended far beyond the pulpit.

In rural Wales, the chapel was the unofficial parliament.

The minister sat in the Sêt Fawr — the Big Seat — facing the congregation beside the deacons like a stern council of elders.

From here, they governed community morality.

The Discipline: Those caught drinking, brawling, or committing adultery were publicly reprimanded or even read out — expelled from membership.

The Consequence: In a village where everyone knew everyone, being excluded from chapel was social exile. Customers disappeared, friends walked away, reputations collapsed overnight.

The preacher held extraordinary social power:

the ability to make or break a name.

Orderly? Yes.

Stifling? Undeniably.

But for a century, it shaped Welsh life more deeply than any landlord or magistrate.

4. Guardian of the Welsh Tongue

Perhaps the preacher’s greatest legacy is one Wales still carries.

In schoolrooms, children caught speaking Welsh were punished with the Welsh Not.

In landowners’ halls, English was the badge of power.

But in the chapel —

Cymraeg was sovereign.

The preacher preached, prayed, debated, and taught in Welsh. Sunday School became a national literacy engine. By the late Victorian era, Welsh working-class literacy rates outstripped many English cities. In countless communities, the first book anyone learned to read was the Welsh Bible.

The preacher preserved the language in its darkest century.

He convinced his people that Welsh was not a remembrance of poverty —

but the language of Heaven.

5. The Radical Conscience of Wales

By the late 19th century, the preacher had become a political force.

The outrage sparked by the Treachery of the Blue Books — a government report that smeared Welsh morality — turned the chapels into political headquarters. Ministers urged their congregations to vote Liberal, challenge landlord domination, and defend tenant rights.

On Sunday, the preacher thundered against injustice.

On Monday, the ballot boxes trembled.

This fusion of faith and political conscience helped forge Welsh radicalism — sowing the seeds of the Labour movement, Welsh Nonconformist politics, and the nation’s enduring instinct to resist injustice.

The Echo That Still Shapes Wales

Walk past a rural chapel today. It may be a house, a community hall, or a slate-roofed ruin sleeping under bracken. The crowds have vanished. The gaslights have dimmed.

But their influence has not.

The high literacy of the Welsh, the passion for choral singing, the political fire, the stubborn survival of the language itself — these are not accidents of history.

They are the echo of the men in black coats who once ruled the valleys.

Men who crowned no kings, raised no armies, and built no palaces —

yet forged a nation in the human voice alone.

Their chapels may be silent.

But modern Wales still speaks with the voice they shaped.