When we think about how people become who they are, we often turn to education, professional training, or moments of career opportunity. Yet the truth is that much of what defines our intellectual and professional identity is sown far earlier – in the unnoticed textures of childhood.

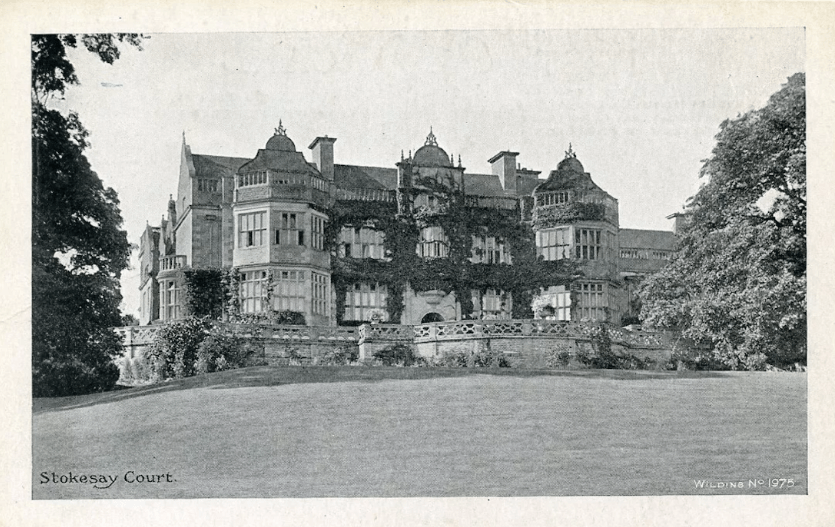

My own journey as a historian was not forged in university lecture halls, but in the fading grandeur of a country house in Shropshire. My parents worked at Stokesay Court – my father as gardener and chauffeur, my mother as housekeeper – and I spent my formative years exploring its corridors, ruins, and archives, absorbing lessons that no textbook could have provided.

The Gentle Influence of Mentorship

One of the greatest influences of my childhood was the famed biographer Sir Philip Magnus-Allcroft. He had no children of his own, yet he possessed a generosity of spirit towards those around him. His encouragement of my curiosity was subtle but profound.

Sir Philip had a routine: before his evening meal, he would change into slippers and summon me with the promise of a chocolate from his desk. But these were not idle rewards. To earn them, I was quizzed on the history of Stokesay Castle:

- Who built the castle?

- Why was it fortified?

Answer correctly, and you were rewarded with a Black Magic chocolate. It was, in essence, my first tutorial. He also gave me my first encyclopaedia and Oxford English Dictionary before I was even ten years old. For him they may have been Christmas gifts; for me they were tools that unlocked a lifelong vocation.

Here was an early demonstration of a truth educational theorists emphasise: that formative mentorship does not need to take place in classrooms. The encouragement of a single adult figure, treating a child’s questions with seriousness, can redirect the trajectory of a life.

The House as a Living Archive

Stokesay Court itself was as much a teacher as Sir Philip. By the 1980s, one wing of the house had fallen into decay. I vividly recall the billiard room flooded by rainwater, cupboards filled with forgotten photographs, and abandoned greenhouses overtaken by plants. To an adult eye these were symbols of decline. To a child, they were portals into the past.

The material culture of a house – the Persian carpets that became race tracks for toy cars, the bell pulls that connected me to vanished servants, the black-and-white photographs stuffed in drawers – all conveyed a lesson: history is not abstract, it is tangible. It resides in the textures of daily life, in objects left behind, in spaces that bear witness long after people are gone.

This early immersion in the material traces of history instilled in me a historical imagination grounded in the ordinary and domestic. When I later came to research the lives of Victorian educators, Welsh tenant farmers, or civic leaders, I was already predisposed to see value in diaries, wills, and personal ephemera that others might overlook.

Childhood Loyalty and the Culture of Service

Equally formative were the older retainers who had lived through the great days of the house. Figures like Mrs Fanny Pinches, who had served as a housemaid since the 1940s, regaled me with stories of earlier generations of the Allcroft family. To a boy she was a grandmotherly presence, offering sweets and companionship. In retrospect, she was also my first oral historian.

Her stories connected me to eras I had never lived through. They gave me not just facts, but values: loyalty, respect for memory, and a sense of continuity. I later realised that her presence also taught me to listen — an underrated but essential skill in both history and leadership.

Memory, Identity, and the Historian’s Craft

Looking back, I see that my professional path was not simply chosen; it was prepared by environment. The ruined wings of Stokesay, the generosity of Sir Philip, the stories of loyal servants, and the ordinary rhythms of life in a great house all converged to form a particular intellectual temperament:

- A respect for material traces of the past.

- A conviction that “ordinary” voices matter.

- A belief that curiosity should always be encouraged.

Educational psychologists often speak of “formative environments” — the idea that our early surroundings embed habits of mind that last a lifetime. In my case, those surroundings were unusual, but the principle holds true for everyone. The workplace, the family culture, the mentors and role models around us in childhood all shape how we later approach knowledge, relationships, and challenges.

Why This Matters Today

Why should this matter to leaders, educators, and professionals today? Because it underlines the long reach of formative influence. The encouragement we give a curious child, the stories we tell, even the environments we create — all of these may shape identities and careers decades into the future.

When we invest in the imagination of children, we are investing in the next generation of thinkers, leaders, and creators. My own path as a historian — writing books on Welsh farming dynasties, Victorian educators, and the cultural values of rural Nonconformity — can be traced back to chocolates in a desk drawer and a crumbling house full of forgotten photographs.

Conclusion: The Enduring Power of Childhood

As professionals, we are often asked to define our career in terms of formal milestones. Yet when I reflect honestly, my true starting point was not a degree or a first job, but the influence of childhood environments.

Sir Philip Magnus never lived to see what I became. Nor did Mrs Pinches or the other loyal retainers of Stokesay. But their influence lives on in my work, my research, and my determination to preserve the memory of lives otherwise forgotten.

So, I end with a question: 👉 What from your own childhood quietly shaped the person — and professional — you are today?