By Antony David Davies FRSA

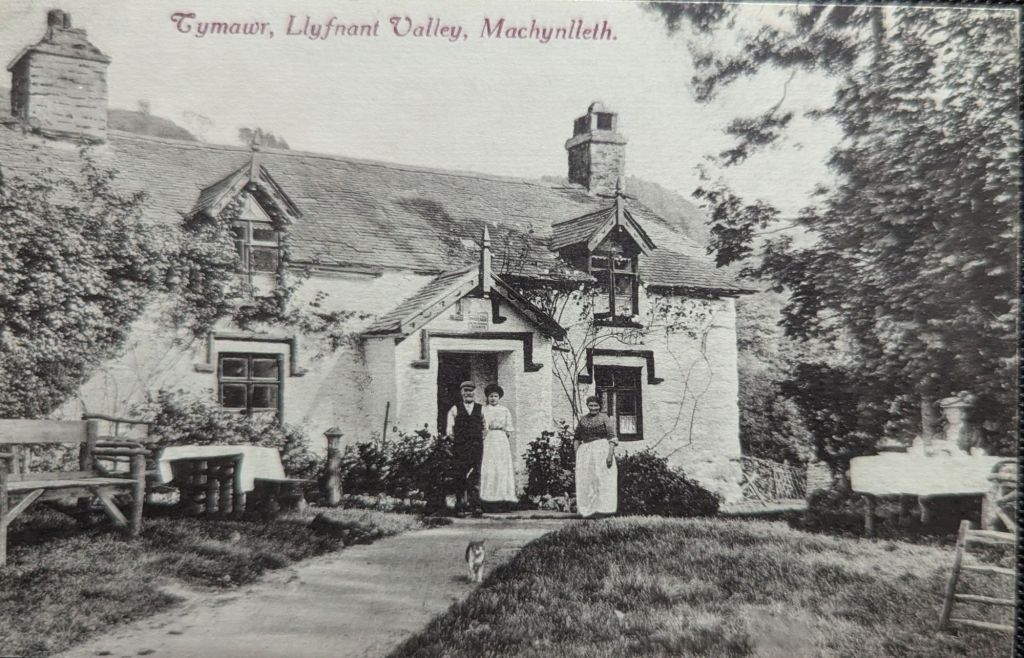

John and Jane Waters, my grandmother’s aunt and uncle, stand with their daughter at the doorway of Tymawr in the Llyfnant Valley — welcoming Edwardian visitors to their farmhouse tea room, nestled in the peaceful hills near Machynlleth.

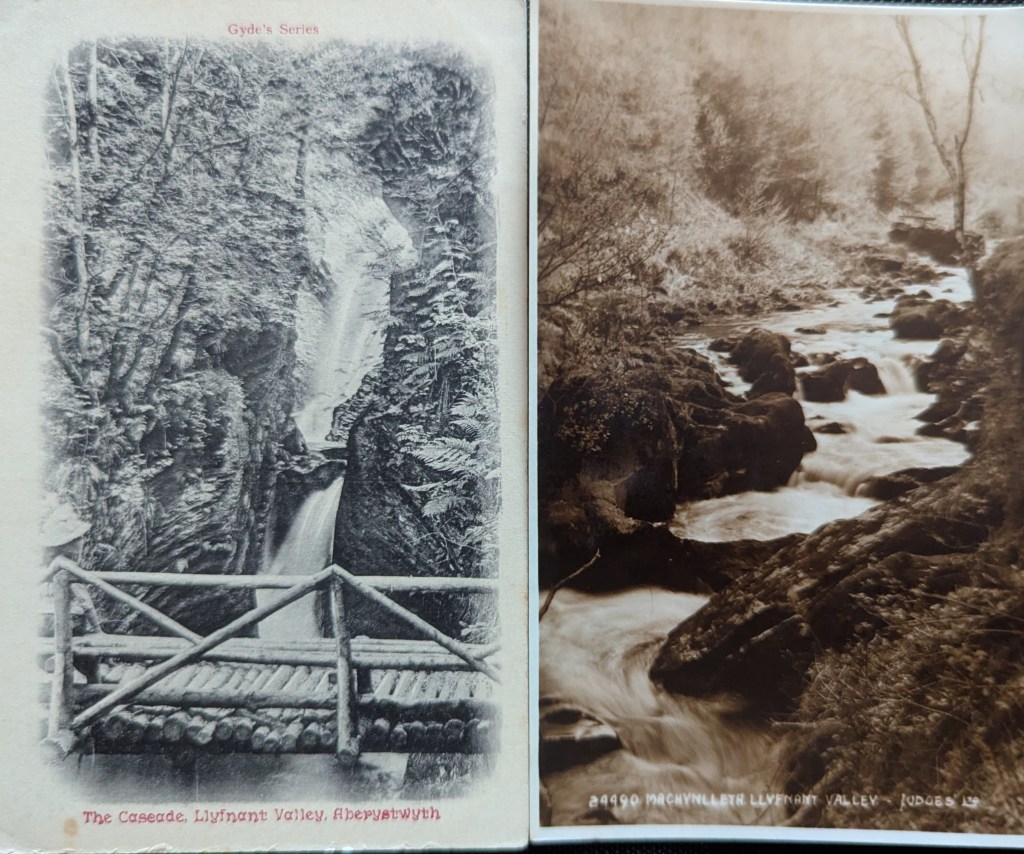

In the remote folds of the Llyfnant Valley in north-west Montgomeryshire—where waterfalls crash through ancient woodland and time seems to move at the pace of a farm horse—a remarkable couple forged a life of quiet industry, community service, and understated innovation. Jane and John Waters, my grandmother’s aunt and uncle, were not landed gentry or political reformers. Yet in their own way, they exemplified the resourcefulness and civic spirit of rural Wales in the Victorian and Edwardian age.

Their story is a window into a lost world: of tenant farmers juggling subsistence with self-improvement, of deacons and dairymaids, of postal orders and Eisteddfod prizes, of modest tea rooms on muddy paths—and of an almost forgotten valley’s fleeting moment of fame.

From Ystrad and Cwmrhaiadr to Tymawr

Jane Jenkins was born on 27 August 1854 at Cwmrhaiadr, a name meaning “valley of the waterfall.” It was a landscape that would define the shape of her life. She was the product of a deeply rooted Welsh farming community—Nonconformist, Welsh-speaking, and steeped in the rhythms of chapel, market, and harvest.

Her husband, John Waters, had been born around 1843 at Ystrad, near Llanfair Caereinion, into the family of Jacob Waters (1815–1894). John’s early years followed a path typical of many rural second sons. With no expectation of inheriting the farm, he left Ystrad to work as a labourer, and by 1871 was employed at Bryncaemisir in Forden. But he was ambitious, and soon secured a position as farm bailiff and gamekeeper at Cae Saer, deep in the Llyfnant Valley—then part of the estate of the Reverend Levi Rees Jacob.

On Christmas Day 1874, John married Jane. By 1879, the couple were tenant farmers at Tymawr, a modest 100-acre holding owned by the Garthgwynion Estate. Though they never owned the land, they made it their home for nearly four decades. Farming in this period was hard and often unrewarded; the agricultural depression of the 1880s hit Wales particularly hard, and tenant farmers like the Waterses were increasingly dependent on diversifying their income and drawing upon community networks.

Civic Duty in the Chapel Tradition

The late 19th century was a time of remarkable civic energy in rural Wales, driven in large part by the influence of Nonconformist religion. Chapel life encouraged literacy, responsibility, and community engagement, and John Waters exemplified this ethos. In April 1879, he was appointed Overseer of the Poor for Isygarreg—a role involving the administration of parish relief to the destitute. It was not a task for the faint-hearted: John would have had to weigh compassion against tight budgets, turning some away empty-handed.

A decade later, in 1889, he joined the Machynlleth Board of Guardians, which oversaw the local workhouse system. Though his attendance at meetings was patchy—perhaps reflecting the demands of the farm—his election indicates the respect he commanded. He also served on the Derwenlas School Board from 1901, and was a long-standing deacon of the Methodist chapel at Glasbwll—a trusted elder figure in a close-knit religious community.

That same community elected (and narrowly rejected) him in various parish and local government elections. In December 1894, he missed a seat on the Isygarreg Parish Council by just one vote. Such elections reflected the growing democratisation of rural governance, following the Local Government Acts of the 1880s and 1890s which gave ordinary Welsh farmers and tradesmen a role in public life once reserved for landed gentry.

Opening Wales to the World: Tymawr as Tea Room

Where John Waters truly stood apart, however, was in his forward-thinking embrace of rural tourism—a trend still in its infancy when he began advertising Tymawr as a destination in 1887. The Cambrian Railways, like many companies at the time, had started to market rural Wales as a romantic escape for urban visitors. The railway station at Glandovey offered break-of-journey tickets to tourists keen to explore the cascades of Glasbwll and the spectacular Pistyll y Llyn waterfall—described by early geologist Professor W. Keeping in 1879 as one of the natural wonders of the region.

Sensing an opportunity, John and Jane Waters opened their tea rooms at Tymawr, offering refreshments, stamps, postcards, and even guiding services to the falls. For a few pence, a visitor could experience a slice of rural Welsh life, and leave with a memento of the valley. For a time, Tymawr even served as the local post office—an anchor for both locals and tourists.

It was a modest but imaginative enterprise, and one rooted in a broader shift in rural identities—from purely agricultural to partially service-oriented. In a landscape previously known only for sheep and slate, John Waters saw the potential for cultural tourism, long before the concept had a name.

Challenges and Decline

Despite these efforts, not everyone was impressed. By 1908, critics were raising concerns about the state of the footpaths and the safety of the walk to the falls. The Cambrian News that year chastised the tenant farmers of the Llyfnant Valley, suggesting they should have invested their tourist profits into improving access. Nor was the valley road in good shape by the time of John’s death in 1917.

Meanwhile, the family was dispersing. Their son David Jenkins Waters, born in 1879, left for London, where he became a dairyman in Hackney—one of many rural Welsh emigrants who adapted their skills to the city. His dairy included a small urban farm and shop, and he employed his siblings John and Maggie. David’s own son, Dr Ifan Richard Waters (1916–2006), would later become a respected GP in southern England.

The family’s youngest son, Evan Richard Waters, stayed at Tymawr and was widely admired for his Eisteddfod singing. His sudden death in 1910, aged just 27, after a long bout of bronchitis, marked the end of any hopes that Tymawr would remain in the family for another generation.

John died in November 1917 of Hodgkin’s disease. His death coincided with a wider waning of the rural tourist trade, hastened by war, poor infrastructure, and changing tastes. Jane left the valley for Machynlleth, spending her final years at Birmingham House, where she died in 1941, aged 87.

A Valley Lost and Remembered

By the 1920s, most of the old family holdings in the Llyfnant Valley—Maescelyn, Alltddu, Tymawr, Ceniarth, Cefnmaesmawr, Cwmcemrhiw, and eventually Gelli—had passed out of the family’s hands. What had once been a close web of kinship and stewardship was slowly unravelled by economic change, rural depopulation, and the end of a certain way of life.

Today, the Llyfnant Valley remains one of the hidden treasures of the Welsh landscape. Narrow lanes wind between moss-covered trees and silent farms. The Pistyll y Llyn still thunders over ancient rock, just as it did when Professor Keeping stood in awe before it nearly 150 years ago. But there are no more tea rooms. No hand-painted signs. No postcards or fireworks to mark a new century.

For a brief time, though, John and Jane Waters gave the valley a voice—serving tea, posting letters, guiding strangers, raising children, and doing what rural Welsh people have always done best: meeting the world on their own terms, with quiet dignity and surprising vision.

—

In memory of John Waters (c.1843–1917) and Jane Waters née Jenkins (1854–1941)—guardians of a valley, and of a way of life now passed.